Crash Course

It’s a safe bet that all law enforcement officers, at one point or another in their career, have taken an accident report.

While it is not a glamorous aspect of the profession, it is a necessary and essential function in law enforcement, according to Boone County Sheriff’s Lt. Chris Hall.

Hall, who joined BCSO’s accident reconstruction unit (ARU) in 2007, speaks from experience on both sides of the fence.

“It’s personal for me,” he explained. “I lost a family member when I was 9 years old. My uncle died in a crash. My father’s sister was in the car as well, her friend was in the car too, and her friend died. It was a double fatality crash.”

The event was extremely damaging to his family, Hall recalled.

“I remember everyone asking why and what happened,” he said. “Those questions stick with you.”

Some years later, Hall approaches his ARU supervisory duties with an inquisitive mindset.

“My approach with my guys is to have them understand that this is someone’s family member,” he asserted. “Our job is to answer the why. We can’t answer every why, but we need to answer as many as we can. We owe it to these families to give it everything we’ve got and report the facts.”

Members of the Boone County Sheriff’s Office’s Accident Reconstruction Unit, from left, deputies Jared Horton and Drew Christian, Sgt. Bryan Curry, Deputy Jeff Nagy, Lt. Chris Hall and Deputy Mike Parsons. BCSO typically works an average of 350 collisions per month. (Photo by Michael A. Moore)

Document, Document, Document

Like most police cases, collision investigations begin with the patrol officer who is first to arrive at the scene.

When a patrol officer arrives, they are the first step in the process. What they do in the preliminary stages of an investigation are crucial to the case, said Lexington Police Department Sgt. Todd Iddings.

“The biggest things are to get the scene secured, identify witnesses, identify the driver of the different (vehicles involved), and decide on impairment,” Iddings said.

The Lexington Police Department is unique in terms of the high number of fatalities it sees in a given year, Iddings added.

“Some smaller agencies may only have five fatals a year,” he said.

To that end, having a patrol officer secure the scene is of the utmost importance, Hall added.

“Responding deputies need to look for specific things out on the roadway,” he said. “When you see tire marks, and they go off the roadway, and the vehicle is down the hill, I need (the deputy) blocking (the marks) off. I can’t have traffic going over it.”

The timetable for having a full-scale accident reconstruction team deployed depends on the agency’s size, Hall said.

For agencies the size of Lexington and Boone County, the response time is reasonably quick as shifts typically have ARU members working.

“Usually, we work various shifts,” Iddings said. “There’s usually somebody working who can respond, get to the scene and figure out what is going on, and then make contact with the coordinator or sergeant of the unit to get additional resources.”

Boone County Sheriff’s Office Lt. Chris Hall demonstrates plotting points using the prism for the agency’s total station. BCSO treats fatality and serious accidents as it would other crime scenes. Hall said the ARU has “… one chance to get it right.” (Photo by Michael A. Moore)

Hall advised that much more is expected during a collision investigation than it was in the past.

“I look at our reports from years ago and what we do now, and everyone just wants more thorough documentation and photographs,” he said. “As a second shift supervisor, I tell my people they have to address many things because they’re going to get called to court two years down the road on these (cases). If they’ve written five or six sentences, they’re not going to remember all of these things. It’s about documenting and taking the extra time at the scene, writing a little bit extra in your report and covering yourself for down the road.”

If an officer doesn’t go into great detail on these reports, more often than not, it will come back to bite them, Hall continued.

“My wife works for some attorneys who represent (insurance companies),” he added. “Many of the things they deal with are injuries from accidents. They do several lawsuits after the fact. One of their complaints is they’ll get officers on the stand, and (the officers) are reading from a two-year-old report that states, ‘Unit one was stopped in traffic and unit two rear-ended unit one.’ It’s very simplistic, but they could have done a little bit more. I tell my deputies to document if they have any injuries. Even if they say it’s minor. Document it. We need to be as thorough as we can.”

Deputies with BCSO work an average 350 collisions per month, most of which are minor fender-benders, Hall said.

Down I-75 in Lexington, that department’s collision reconstruction unit has worked 24 fatalities, including eight that turned into criminal cases, from January 2019 until mid-September, Iddings said.

No police agency is immune to collision investigations. The University of Kentucky’s Transportation Center performed a five-year (2012-2016) analysis on traffic crashes across the state. The study found state law enforcement officers worked between 91,205 (2012) and 116,160 (2016) collisions in a given year. Of those, 3,416 were fatalities.

According to data from the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, 724 people died in vehicle collisions in 2018. Therefore, the need for thorough investigations is a must, Hall said.

“We treat every fatality accident and serious physical injury or deemed life-threatening accident seriously,” Hall continued. “We tell (deputies) to handle it like a crime scene because, until proven otherwise, we don’t know what we have. We have one shot at getting this right.”

An officer’s attention to detail is vital, whether it be in a homicide investigation or collision investigation, Hall added.

“It may be something as small as a filament in a headlight,” he said. “It’s importance could make or break the case.”

Improved Technology

From Total Stations to 3D Scanners, law enforcement officers have many state-of-the-art tools available at their disposal for collision investigations.

In recent years, automotive companies have also stepped up their game in terms of technology that aid law enforcement in collision investigations.

One of the most helpful pieces of technology, now standard in most vehicles, is the Event Data Recorders (EDR), also known as the “Black Box.”

Lexington Police Department Sgt. Todd Iddings said his department’s collision reconstruction unit holds bi-monthly training to sharpen skills. The training typically includes reviewing recent cases and seeking team members’ input. (Photo by Jim Robertson)

“We can mine that data from the EDR,” Iddings said. “We can do math work on (the data) to figure out speeds. If you have only one car with an EDR, but you have one set of good EDR data, you can figure out what the other car was doing. Most cars have EDR since the mid- to late-2000s. It is hit or miss before that.”

Every manufacturer’s EDR has a different set of data it captures, Iddings added.

“Some have engine RPMs, and most all of them will tell you if the seatbelt was in use,” Iddings said.

If airbags are deployed in a collision, most EDRs will go back five seconds before the crash and record various data points.

“The biggest piece of information from EDRs is the change of velocity, the Delta V,” Iddings said. “It will tell you what the vehicle’s speed was five seconds before the collision.”

Hall echoed Iddings’ thoughts on EDRs.

“It’s wonderful technology,” he stressed. “I’m utilizing one in an active manslaughter case I’m working. With the data, I can look at a defense attorney and say, this tells me the person was doing 107 mph in a 45 mph zone five seconds before the impact. The look on the defense attorney is absolutely great. It deflates their balloon because they can’t argue against the data.”

Aside from EDRs, Hall said many people are now using dash-mounted cameras, which have proven useful in collision investigations.

“Last year, three of our reconstruction investigations had actual dash-cam footage from the parties involved,” he explained. “We’ve seen an uptick in citizens doing that. About a week and a half ago, there was a claim about a person who stopped at the light and was rear-ended. The other person said, ‘No. He rolled back into me.’ He had a dash-cam that disproved the claim altogether. It’s helpful. You can’t argue with the footage.”

Department of Criminal Justice Training Law Enforcement Instructor Charles Nichols said vehicle technology is a valuable tool for collision investigations.

“As new cars come out, more and more technology is available, which will make it easier for us,” Nichols said. “There are whole classes on data recorders out there. At the end of the day, you don’t use (data recorder information) as definitive evidence, but it can support your findings.”

Playing Well with Others

At a collision scene, law enforcement is one piece of the puzzle. More often than not, law enforcement, fire departments and emergency medical services are working at the same time on the scene, and amid the chaos, the evidence is trampled.

Iddings and Hall said working with fire and EMS personnel is necessary given the broad scope of public safety.

“We call the fire departments the evidence eradication units, it’s a running joke in police work,” Hall jested.

Joking aside, Hall said the role of fire departments and EMS are essential too.

“There are certain times they’re going to have to do things, but they have to do what they have to do, he said. “Sure, I don’t want them to cut the roof off a car because I can use that in the investigation. However, they may have to do it to get the people out. It’s something we have to deal with.”

Iddings echoed Hall’s thoughts.

“Our first job is public safety and to preserve human life,” he said. “When we have car wrecks, fire and EMS are going to respond and their thought process is to help the victims.

“They’re not going to park 300 feet back to make sure they’re not driving over evidence,” Iddings continued. “They’re going to get the resources they need to the vehicle … we let them do their thing and when they leave, we do our thing.”

Training

Aside from formal reconstruction training, both Hall and Iddings’ departments conduct training for members of the reconstruction teams as well as members of the department as often as they can.

“We do periodic roll-call training,” Hall said. “We have a PowerPoint presentation that we do at roll calls. We try to do it every quarter. It’s about a 20-minute presentation, and it goes through what we expect as a reconstruction unit from the responding officer. It also addresses what supervisors should do.”

The training at BCSO goes into detail about the should and should nots of a patrol deputy.

“It’s something most road deputies do not know – that if the airbag does not go off, that data is not locked in the EDR,” Hall said. “So, if they move the car or do something drastic, data can be lost. Responding deputies need to look for specific things out on the roadway, and we have pictures in our roll call presentation.”

As second-shift supervisor, Hall also has one-on-ones with deputies.

“On a shift, I will take the opportunity to teach guys when I can,” he said. “I explain this is what I’ve seen on their reports. I will say, ‘Hey, next time do this.’”

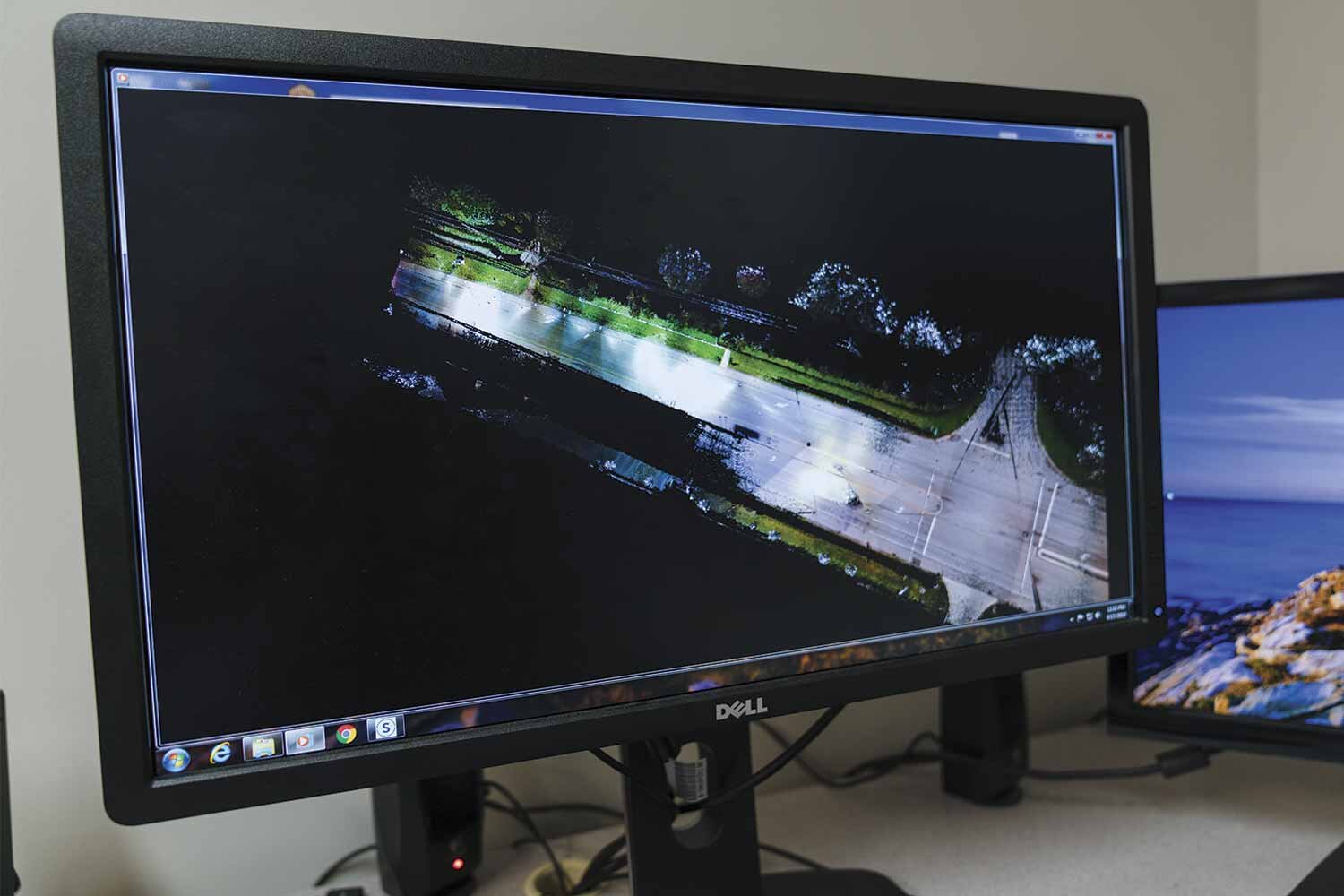

Lexington Police Department Sgt. Todd Iddings shows the detail in a scan from the department’s 3D scanner on the computer screen. Through mid-September 2019, LPD has worked 24 fatalities, eight of which turned into criminal cases, Iddings said. (Photo by Jim Robertson)

In Lexington, the collision reconstruction unit conducts bi-monthly training, Iddings said.

“We walk through our cases and get everyone’s input,” he explained. “We talk through, physics-wise, the best way to figure out speeds, the direction of travel, approach and departure angles and things like that. It’s a lot of math practice. We come up with problems, give a scenario and figure out the math on it.”

Training and honing skills is necessary, Hall said.

“This is something that if you don’t practice it often, you’ll forget it,” he said, referring to the vast number of math formulas needed to perform the job.

Like nearly every area of police work, the specialty of collision investigations is continually changing, especially in the area of technology, Hall opined.

“As a team, we have to foresee where technology is taking us and prepare for that,” he explained. “We have to understand the direction this field is going. I became a reconstructionist in 2007. What I learned then has changed. What I learned now will change in the next 10 years. We have to stay ahead of the curve.”

It is essential for law enforcement personnel who may not be a part of reconstruction teams to know how to proceed when they arrive on the scene. To that end, DOCJT will offer a collision investigation course starting in 2020.

“In other words,” Nichols said, “it will address things to think about when they first get there.”